The Songdo Bypass Highway Construction – Are We Asking the Right Questions?

By Steven F. Bartlett, Associate Chair, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Utah Asia Campus, Songdo, Yeonsu-gu, Incheon Korea.

The search for viable solutions to complex societal problems forces us to question. The process of formulating, exploring, and ultimately answering the “right” questions is paramount to rational decision making. To this point, the following statement has been attributed to the renowned Albert Einstein. “If I had an hour to solve a problem and my life depended on the solution, I would spend the first 55 minutes determining the proper question to ask… for once I know the proper question, I could solve the problem in less than five minutes.”

Asking and answering the “right” questions brings clarity to complex decision making and maximizes the chance of obtaining sustainable solutions. This approach is not only fundamental to the scientific method but is crucial for good public policy and decision making. Perhaps a consistent framework for evaluating the efficacy of questioning is to categorize questions as good, better, and best. Good questions are useful and lead to follow-up questions or better questions. These, in turn, ultimately produce the best questions, or the right questions suggested by Einstein

I wish to apply this approach to the development and design of a transportation project that is currently in the planning stages by the Korean Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transportation (MLIT) in Songdo, Yeonsu-Gu, Incheon (Fig. 1). Under the current MLIT plan, part of the proposed maritime bridge (i.e., elevated, pier supported highway) and interchange connecting to the Incheon International Airport will be situated along the scenic West Sea coastline. However, this proposed alignment crosses environmentally sensitive and protected mudflats north of the planned elevated interchange (Fig. 1). The International Ramsar Convention has recognized this 2.5 km2 wetland as a habitat for endangered migratory birds. Also, many Songdonians oppose the construction of the elevated highway along the shoreline because it will block scenic seaside views and increase noise and pollution in planned residential/recreational/commercial areas along this stretch of the West Sea coastline.

Fig. 1 Songdo elevated highway and interchage proposed by MLIT (circled in red). Ramar wetlands approximately located in blue polygon.

Nonetheless, MLIT has justified its position to proceed with the planned elevated highway and interchange based on its project evaluation criteria consisting of (1) cost, (2) user benefit, and (3) non-user benefit. Cost criteria include construction/land compensation costs and maintenance costs. User benefits include reduced vehicle operating costs, reduced operating time (i.e., travel) time, reduction of accidents (safety), and increased driving comfort. The sole non-user benefit listed is noise considerations (i.e., noise mitigation due to the new infrastructure). Questions regarding how to reduce cost, improve highway user, and non-user benefits are “good” questions, but by themselves are not sufficiently comprehensive because they are narrowly focused. These MLIT evaluation criteria include issues related to project construction, user and maintenance costs, user safety, and traffic efficiency. However, they lack evaluation criteria that specifically address protection of the environment and ecological habitats, and how to preserve and enhance open spaces for multipurpose use. Because the current MLIT benefit/cost (b/c) evaluation does not consider green and sustainability criteria, the selection process is biased. For projects such as the Songdo Highway, better questions should be formulated and evaluated.

For example, many Departments of Transportation in the United States have adopted more comprehensive evaluation criteria. One notable example is a self-certification program called GreenLites (Green Leadership in Transportation Environmental Sustainability) approved by the New York State Department of Transportation. Its overall goals are:

Protect and enhance the environment

Conserve energy and natural resources

Preserve or enhance the historic, scenic, and aesthetic project setting characteristics

Encourage public involvement in the transportation planning process

Integrate smart growth and other sound land-use practices

Encourage new and innovative approaches to sustainable design and how to operate and maintain facilities. (https://www.dot.ny.gov/programs/greenlites)

Perhaps the design and construction of the Songdo Elevated Highway can serve as a test case to develop and adopt a more comprehensive evaluation process such as GreenLITES. The possible inclusion of objectives similar to those of GreenLITES would significantly transform the transportation planning and design process used in Korea. The potential changes would substantially modify an outdated method to a 21st Century model that has sustainability and green infrastructure as its core values. Thus, in addition to evaluating questions about cost reduction, safe traffic operations, and efficiency, MLIT could begin to explore: (1) How might the transportation project protect or enhance the environment? (2) What steps are needed to conserve energy and natural resources? (3) How might the project improve the scenic and aesthetics of the area? (4) How can the project encourage and incorporate public input? (5) Has growth and sound land-use practices been adopted, including principles of green infrastructure and multiuser benefits? (6) What considerations have been taken to encourage sustainability in the operation and maintenance of the transportation facilities?

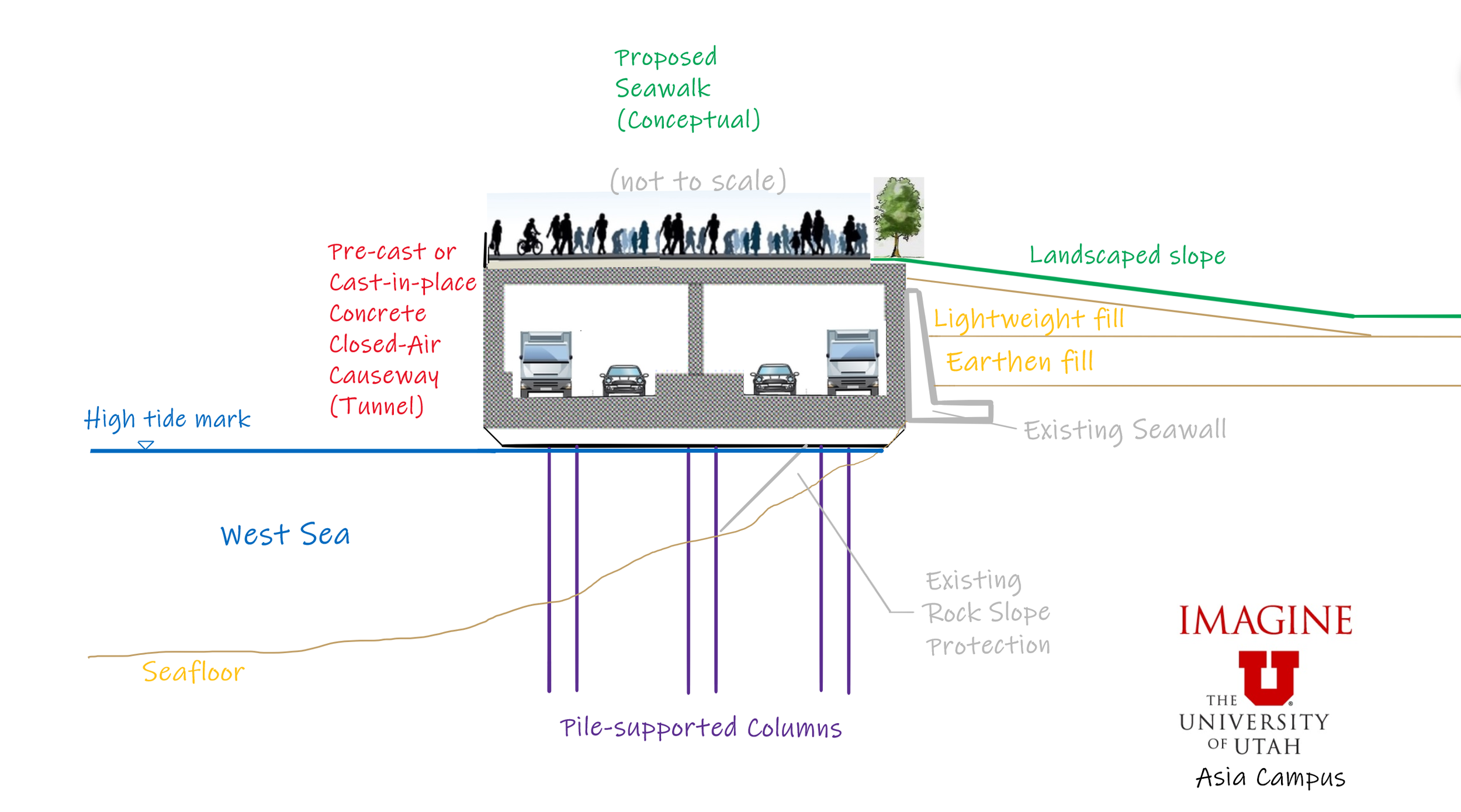

In an informal meeting with MLIT, the engineering and urban ecology faculty of the University of Utah Asia Campus (located in Songdo) proposed more green and environmentally friendly alternatives. These included moving the alignment to parallel the existing sea wall as an enclosed highway (Fig. 2) and locating the proposed interchange from the wetlands to an area further to the north. We also proposed that a sea walk/seaside park be created on the roof and side slopes of the enclosed highway for recreation. With these potential changes to the masterplan, the impacts on the marshland will be significantly reduced, unobstructed views of the West Sea will be preserved, traffic noise will be eliminated, and additional recreational space created for the residents of Songdo. These recommendations appear to have gained popularity in Songdo based on numerous chat board discussions and “likes.” No doubt, there are engineering and environmental issues that need to be resolved to implement such concepts. However, all appear to be within the capabilities of the various professions to do so.

Fig. 2 Proposed enclosed highway with sea walk and park situated along existing coastal seawall.

Unfortunately, based on the discussions during this meeting, it was clear that MLIT project planners remained entrenched in the philosophy of the current MLIT benefit/cost system. Nonetheless, it is my opinion that the MLIT, encouraged by the public and others, should implement a more comprehensive planning and design framework for this project. We should do so out of respect for the environment, and the protected and endangered species therein. The Songdo West Sea Coastline is worthy of our protection and preservation. It heals our souls and deepens our connections with nature. It is time to ask the best questions that will lead to better and more sustainable solutions.

Songdo mudflats looking toward Incheon Airport Bridge

Benefits of Enclosed Highway

Seawalk Possibilities (1)